Background of the American China project

My first encounter with Chinese American history was not through any textbook in school but from a middle school assignment to collect my grandparents’ oral histories. As my grandfather recounted the long history of our family that went back to the beginning of the 1900s, I remember my father being surprised by details as new to him as they were to me. I would later learn what seemed so impossible and unique to our family was a near-prototypical story of the Chinese American journey during the early 1900s.

Today, decades later, I reflect back on my family history and my own Chinese American identity and think about how I’d like to pass this history to future generations. As language and customs slowly fade, food has always been at the core of my Chinese American identity. I thought the most appropriate medium for this part of my family’s history would be food-related and thus the most appropriate setting would be the dinner table.

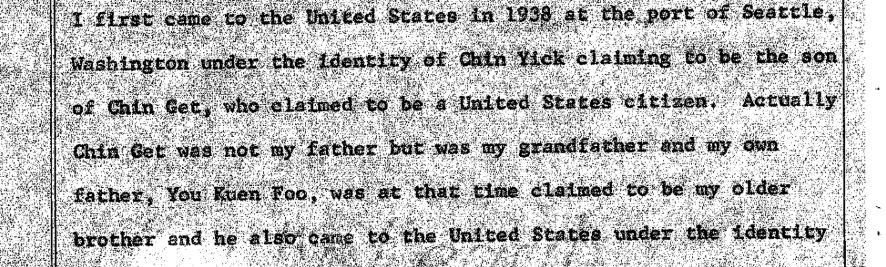

My idea was to encapsulate significant parts of my family history into pieces of porcelain dinnerware that I can incorporate into my daily life. The goal is by creating pieces that are both usable yet physically compelling, I can initiate and facilitate conversations about family and Chinese American history at the dinner table.

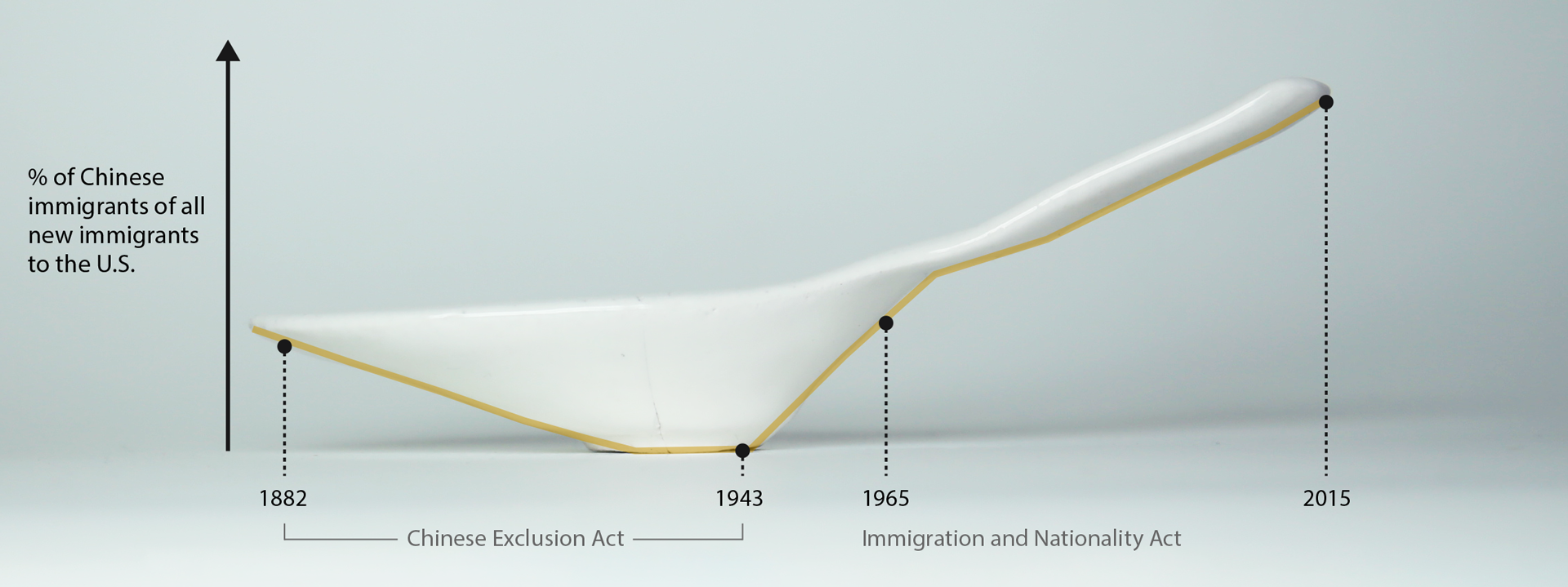

The first piece I designed was a traditional soup spoon. The spoon was inspired by the time at which the first of my family immigrated to the United States.

I am fifth generation Chinese American on my father’s side and third generation Chinese American on my mother’s side. The first to arrive to the United States was my great great grandfather on my father’s side, Foo Tai Yen, who entered through the west coast at the turn of the 20th century. During that time, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred all immigration of Chinese laborers, has been in place since 1882 and became permanent in 1902. Since Tai Yen was not an exception to this law, he entered the country by illegally purchasing papers that changed his family name from “Foo” (傅) to “Chin” (陳).

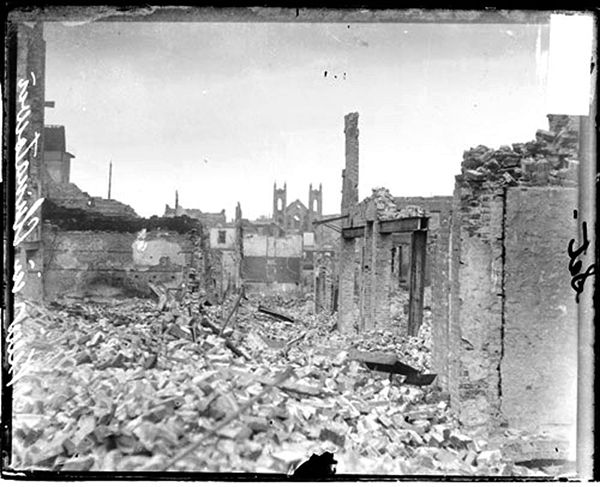

Tai Yen immigrated to Chicago which was a popular city for the villagers from his region, the Xinhui district of the Guangdong province, to congregate. It was around that time, the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 struck and killed up to 3,000 people and destroyed over 80% of the city.

Source: Chicago Daily News/Wikimedia Commons

The earthquake, however, had the unintended effect of opening a new immigration window for the Chinese in America. As fires destroyed much of the city, the birth and citizenship records were also destroyed. The loss of these documents allowed many Chinese immigrants to claim they were born in San Francisco rather than China, thus granting them U.S. citizenship. This opened the door for the purchase and sale of fraudulent documents which stated that Chinese immigrants were blood relatives to Chinese Americans who had citizenships in the United States. Recipients of these documents were referred to as Paper Sons.

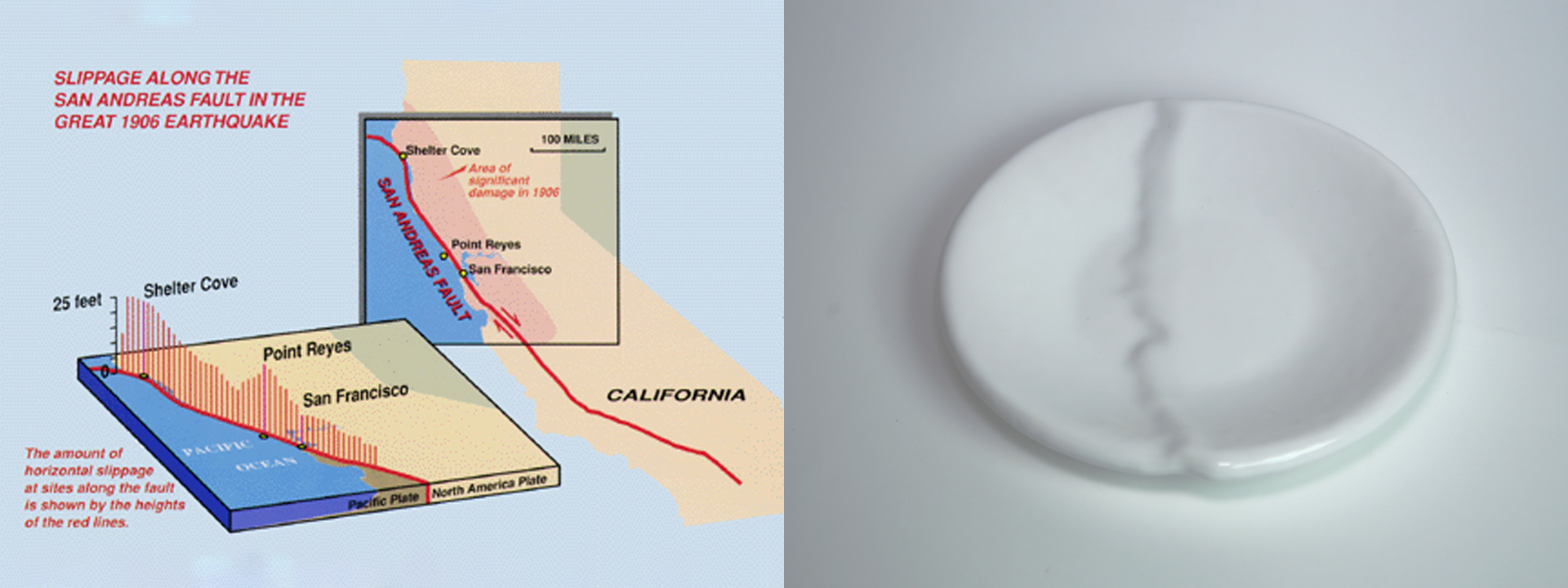

Tai Yen, taking advantage of the situation, reported to the authorities that he had six children, thus insuring he could bring other family members over in the future. This event inspired the next piece, the plate, which used actual data from the 1906 earthquake to make a subtle crack down the center.

Like other immigrants, Tai would work in the United States for a few years and return home for a month or two and then return back to the States. On one trip, he had brought his eldest son Fook Poy (Harold) back with him to the States. Then on another, he brought his other son, Harry. On his last visit in 1939, his grandson and my grandfather, Sui Him (Allen) had accompanied him on the long journey back to the States.

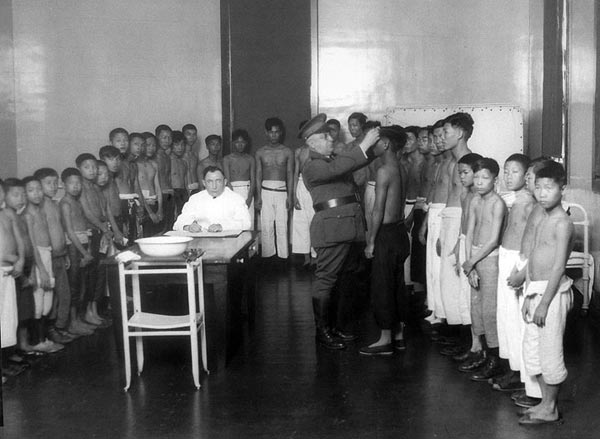

Sui Him crossed the Pacific Ocean on an old steam ship to Vancouver, took a ferry to Seattle, and finally landed in Angel Island in San Francisco. Sui Him had to claim to be the younger brother of his father to match the papers claimed by his grandfather, Tai Yen. He was detained for two weeks at the immigration station in Angel Island until his interview with the immigration officers.

At this time, Chinese detainees were subject to physical exams, lengthy interrogations, and often long detentions, from weeks to months, aimed at upholding the exclusion laws that kept Chinese out of the country. The Paper Sons phenomenon only made exams and interrogations longer and more elaborate.

Source: National Archives

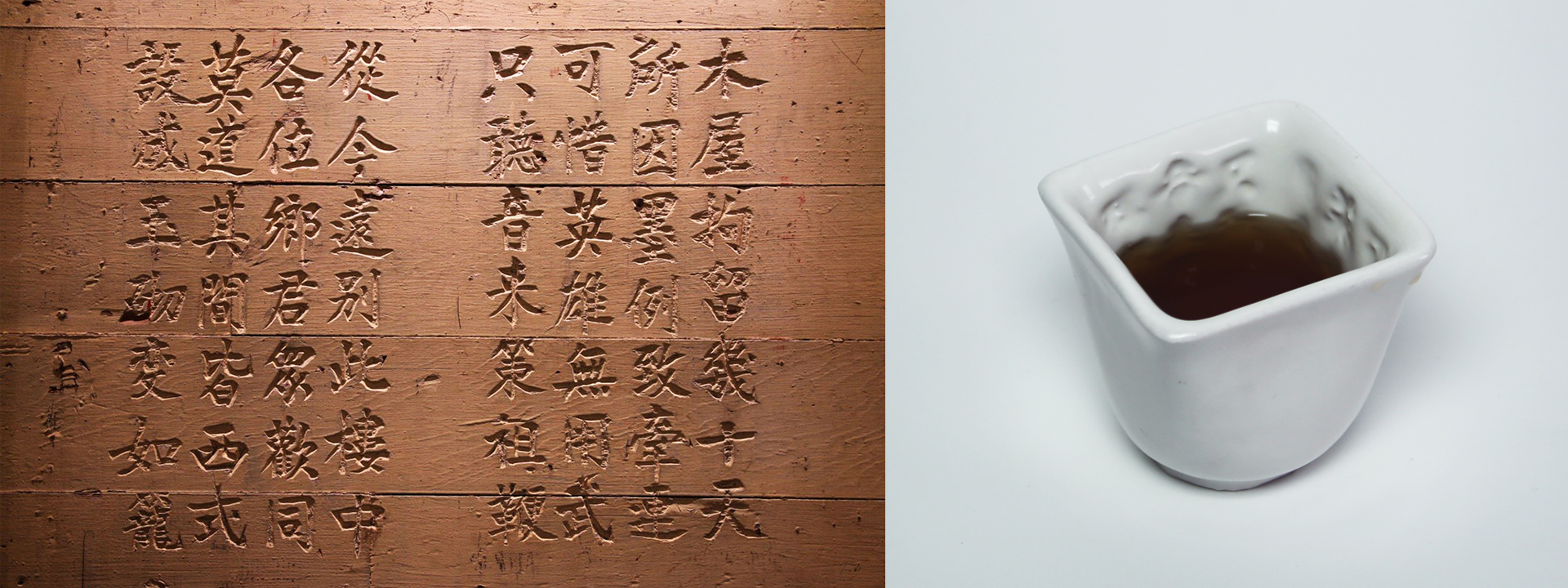

Forbidden to communicate with the outside world, many detainees recorded their experience in poetry written and carved on walls of the immigration station. Over 150 of these poems were later translated and annotated. Many who left their marks were Cantonese villagers in their late teens who, despite having no more than a grammar school education, implemented classical forms of Chinese poetry, such as the seven character quatrain. This inspired the next piece, a tea cup with an excerpt from an actual poem engraved on the walls of the Angel Island immigration station.

Photograph by Mak Takashi.

Luckily for my grandfather, his story matched what his grandfather had said. He then started an 18-day journey across the United States through Seattle, Chicago, New York City, and finally New Jersey where his grandfather opened a laundry business, the most popular business for Chinese immigrants since the gold rush in the mid 1800s which, in many areas, was almost exclusively a Chinese enterprise. This was largely due to a laundry’s low start-up cost as it minimally required a scrub board, soap, and an iron with no special training. Racial discrimination also played its part as Chinese Americans were kept from more desirable careers and pushed towards undesirable service-oriented professions such as cooking and cleaning which were considered undesirable occupations by Euro-Americans.

Chinese Laundries: Tickets to Survival on Gold Mountain by John Jung

Sui was quickly moved into the laundry business and worked along side with his father, grandfather, and uncle. In the front of the store were the tools of the trade: hand irons, water sprayers and ironing board. The shirts were neatly hung by the window ready to be picked up by the customers. A wooden partition separated the place of business from the living quarters. In the back, next to the wooden washing vats, was the sleeping quarters. His father, Fook Poy, said some day he will go back to China and have the white men do his laundry.

This is where my memories meet my grandfather’s oral histories, as I have very distinct memories of my grandparents’ home and laundry. This also inspired the last piece in this project, the tea pot, which is modelled after a traditional hand iron.

Photograph by Museum of Chinese in American

I end this project in 1943, five years after the arrival of my grandfather to the United States. 1943 marks the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, over 60 years after its enactment when China was seen as an ally against the Japanese in World War II. In the decades following, the remainder of my family, including my great grandmother, grandmother, and aunts, would arrive in the United States.

My grandfather would officially change our family name from Chin (陳) back to Foo (傅) after submitting a written confession on behalf of his grandfather through the Chinese Confession Program which claimed to offer legalization of status in exchange for confessions of illegal immigration during the Exclusion Act.

These pieces just scratch the surface of Chinese American history and my family history. I hope these pieces provide daily utility and an occasional catalyst for conversations about an easy-to-forget part of American history.